She hitchhiked to Italy to learn from the best sculptors - now she takes care of Denmark’s castles

It’s often said that you can write yourself into history - but Mette Marciniak Mikkelsen quite literally carves her way into it. As a stonemason and sculptor, she has the rare ability to transform raw stone into works that will endure for centuries. And that skill is in high demand as Denmark’s castles face extensive restoration work.

By Anna Skovby Hansen

With hammer and chisel in hand, Mette safeguards Denmark’s cultural heritage - one strike at a time. Her master once told her she should go home, get married, or attend domestic science school instead of becoming a stonemason. But a stay in Italy gave her both confidence and strength, and since then she has carved out a place for herself as one of the few Danes with the expertise to restore some of the nation’s castles and museums - from Fredensborg Palace to Kunsten Museum of Modern Art in Aalborg.

»Being a stonemason is also being a storyteller,« says Mette Marciniak Mikkelsen, who today works as a restoration architect.

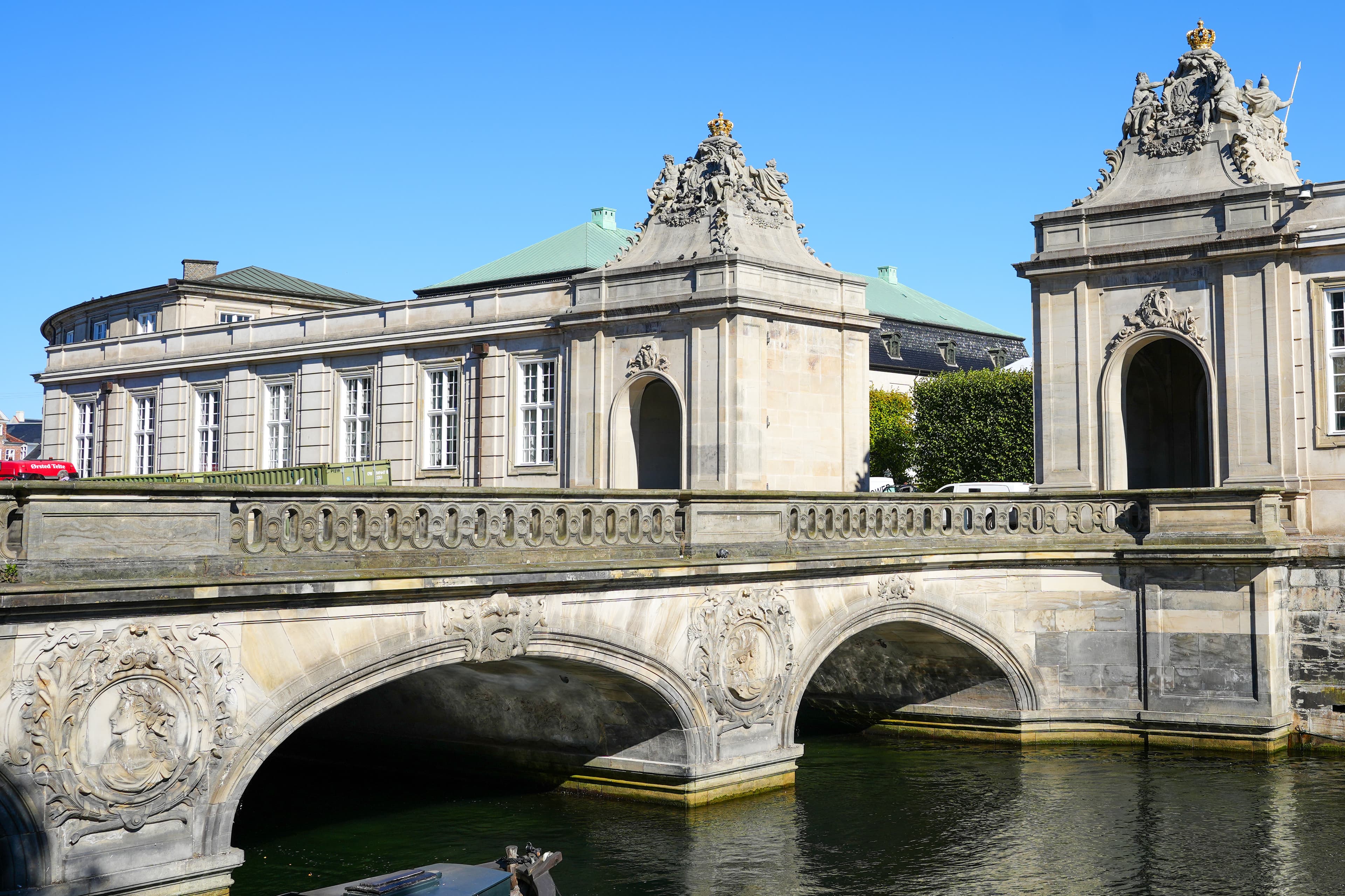

It’s a clear autumn day, and we crane our necks, squinting up toward the cloudless sky that makes the sandstone and sculptures of the Marble Bridge’s pavilions glow in the sunlight.

Mette points upward toward the ornate decorations.

»I want to be able to show my great-grandchildren and grandchildren and say, ‘This - this was made by Grandma.’«

Mette Marciniak Mikkelsen is 57 years old. She is a trained stonemason and restoration architect from the Royal Danish Academy. Today, she runs SANDSTENSRESTAURERING A/S – Consulting & Craftsmanship in collaboration with Vallø Foundation. Alongside that, she manages MARCINIAK Restoration, where she works as an architect specializing in stone and sculpture restoration.

The Marble Bridge Pavilions Get a New Life

One of the projects Mette has worked on most intensively is the restoration of the Marble Bridge pavilions at the Christiansborg Riding Grounds in Copenhagen. The bridge connects Slotsholmen to the rest of the city across Frederiksholm Canal, and if you look up, you can see the statues gazing out over the water.

Each pavilion is crowned with a royal emblem - the king and queen’s monograms carved beneath, and swirling leaf motifs climbing the pyramid-shaped tops. In every detail, you can see the results of, among other things, Mette’s five years of work as a stonemason on the pavilions.

»In my work, I get to protect and pass on our cultural heritage. It doesn’t get much better than that. It’s incredibly exciting to work in a craft with such deep traditions - and such few tools,« Mette says.

The tools are simple - a hammer and a chisel - but the work is physically demanding. With the right technique and patience, those tools can transform a raw block of stone into anything from columns to sculptures.

»When you’re learning to carve stone, you spend the first year hitting your own hand. One arm becomes one big blood blister,« Mette recalls, thinking back to her apprenticeship days.

She explains that it’s usually those with a strong sense of form who carve sculptures and decorative elements.

»I can almost sense the figure inside the raw stone - it just needs to be carved out,« she says, noting that this was also how Michelangelo used to describe it.

"Of course I’ve gotten comments about being a female stonemason - but as soon as people see what I can do, they usually gain respect for my work."

Hitchhiking to the Heart of Marble in Northern Italy

When Mette stands today gazing at the restored figures atop the Marble Bridge pavilions, she does so with a calm confidence that only comes from years of experience. But her journey began far from the sandstone and royal ornaments of Christiansborg - in the back of a truck leaving from Glyngøre.

On the passenger seat, traveling down through Jutland and across the German border, sat Mette with a backpack containing her most essential tools: a hammer and a chisel. She was just 21 years old and newly trained as a stonemason. In her luggage she carried a bronze medal from her apprenticeship exam - and a deep sense of adventure.

It was her hunger for something new that led her to hitchhike through Europe until she arrived in northern Italy, where she knocked on the door of the Danish sculptor Jørgen Haugen Sørensen, whom she was to work for.

»He was the great role model - the one everyone dreamed of working for,« she recalls.

Stonemason and Sculptor

A stonemason has a craft-based background, trained through a vocational education where precision, technique, and tradition are at the core. The stonemason works natural stone into architectural elements, staircases, gravestones, and restoration projects.

A sculptor, on the other hand, works primarily in the artistic realm, creating sculptures and decorative works where form, concept, and expression take center stage. The education is typically art-based - for example, at the Royal Danish Academy.

In the Footsteps of Michelangelo and Thorvaldsen

Mette’s years in Italy would come to shape the rest of her career as a stonemason. There, she built a community of fellow artisans and met some of the world’s most skilled sculptors and stone carvers.

It was in this environment - surrounded by marble dust and mountain air - that she truly refined her technique. In the mountains of northern Tuscany lie the Carrara marble quarries, a place that has attracted artists for centuries. Stone has been extracted there since Roman times, and its fine white marble has been used in some of the world’s most famous works of art.

»Michelangelo and Thorvaldsen both got their marble here. But it’s also a place where artists from all over the world come to have their sculptures carved,« says Mette.

One of the most famous works created from Carrara marble is Michelangelo’s David. In those same mountains, Mette learned to master her own artistic expression and perfect her technique. She traveled for two years with Jørgen Haugen Sørensen, serving as something of a right-hand assistant.

»You’re utterly exhausted - it’s incredibly hard, physical work. I wore wool underwear until spring because it was so cold standing outside all day, and the carving made you unbelievably dirty. When I came home late in the afternoon, I’d always take a nap - but often, I wouldn’t wake up again until my alarm rang at six the next morning,« Mette recalls.

Too Lanky to Be a Stonemason

Mette first discovered the craft of stone carving thanks to her father. Already in elementary school, she dreamed of becoming an architect, but her father lovingly encouraged her to get a craftsman’s education first.

»You can never go wrong with a trade,« he used to say.

»My father was a bit old-fashioned. He said you could feed pigs with all the architects who didn’t have a craft background - because you need to know what you’re working with,« Mette recalls.

But Mette faced resistance early on. At just 17 years old, when she began her apprenticeship as a stonemason in Skive, she was met with skepticism.

»They looked at me and said, ‘You’re too tall and lanky - you’ll never be a stonemason.’«

She remembers one day on the construction site when she spilled a wheelbarrow full of concrete.

»Then they told me I could go home, get married, or attend domestic science school.«

But Mette stayed. She kept working, learning, and proving herself.

»There were so many prejudices along the way. When I finished, I was only the third female stonemason ever trained in Denmark,« Mette says.

»Of course, I’ve gotten comments about being a woman in this field - but once people see what I can do, they usually develop real respect for my work,« Mette adds.

Lifelong Learning

The dream of becoming an architect had never completely let go of Mette. So in 1995, she decided it was finally time to apply to architecture school. Without a high school diploma, she had to request a special exemption - but her extensive professional experience spoke for itself, and she was accepted. At the same time, she had two small children at home to care for, and on top of that, she won a commission to carve a sculpture for the National Museum in Stockholm.

»I thought, well, this probably isn’t ideal - I had so many things going on. But I just knew that sculpture was something I had to make« Mette says.

The sculpture depicts Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, the Swedish Baroque architect behind Stockholm Palace. It was carved from the finest white marble and stands nearly three meters tall.

»I had to work weekends and never took vacations, but it was worth it. The only real downside of being a craftsperson is starting work at six in the morning - or earlier,« she says with a smile.

»I’ve always followed what I’m good at - and what makes me happy,« Mette adds.

As she explains, craftsmanship is as much mental as it is physical - it’s about having faith in your own abilities.

»You can’t be afraid of the stone - if you are, you’ll never finish« Mette says.

»If you’ve got a bit of a hangover, you don’t stand there carving tiny details on a fingertip. You work on the back of the sculpture instead. Many of us save the rough work for days when we grab the big hammer and chisel and knock off a lot of stone. And on other days, when the classical music is playing, we focus on the finer details - the nails, the polishing,« Mette explains.

After completing the Stockholm National Museum project and graduating from architecture school, Mette joined the Danish Agency for Culture and Palaces, where she worked for 17 years. There, she helped preserve and restore some of Denmark’s most significant historic buildings - including the royal palaces.

Today, she runs her own company, working on restoration and sculpture projects at manors and castles across Denmark.

Udvalgte projekter

Fredensborg Palace

For her work on the sculptures in the gardens of Fredensborg Palace, Mette and her colleague received the prestigious Europa Nostra Award - a European prize honoring outstanding projects that preserve and protect Europe’s cultural heritage.

The Marble Bridge

At the Marble Bridge Pavilions, Mette worked as a stonemason - a project that spanned five years. During that time, she helped carve the royal monograms and the ornamental leaves that spiral gracefully up the sides of the pavilions.

Designmuseum Denmark

Another example of Mette’s work is the restoration of the facade and sculptures at Designmuseum Danmark, where she contributed her expertise in stone conservation and craftsmanship to help preserve the museum’s historic architecture.

Kunsten Aalborg

Mette draws on her expertise as both a stonemason and a restoration architect. Her combined knowledge of traditional craftsmanship and architectural restoration allows her to contribute to projects that honor the original design while ensuring the building’s longevity for future generations.

The Guardian of the Castles

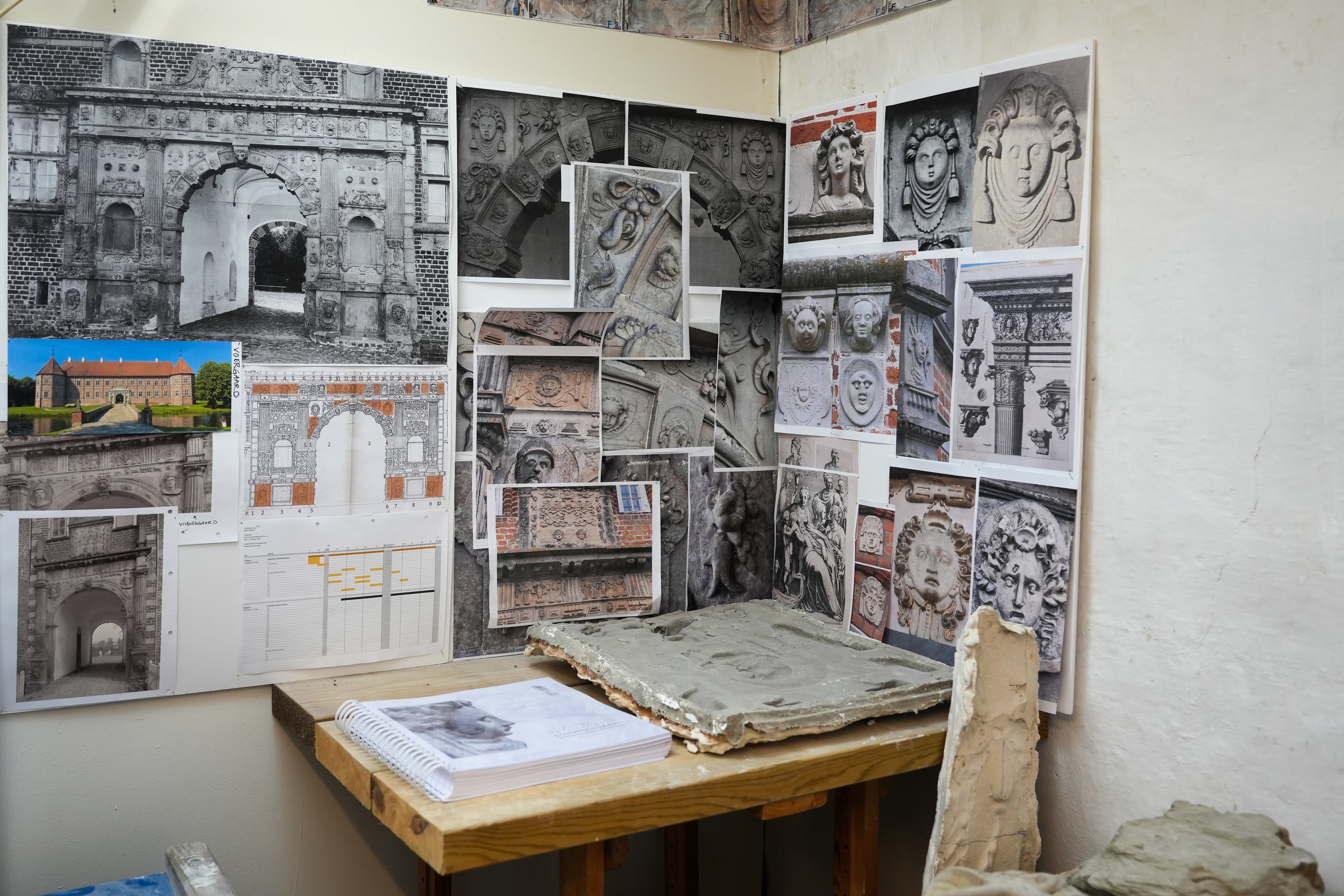

A few days after our meeting at the Marble Bridge, Mette opens the door to her workshop in a small house next to Vallø Castle, just across the moat. Here, she runs her company Sandstensrestaurering (Sandstone Restoration) in collaboration with Vallø Foundation, focusing on the restoration of natural stone

The workshop is a perfect mix of creative chaos and order. Reports, books, plaster models, chisels, easels, hammers, and small figures cover the tables - arranged in a system understood only by Mette and Jens, a sculptor from Germany who works with her on the Vallø Castle project. Jens speaks only German, so Mette switches effortlessly between half-Danish and half-German when they talk. Yet one thing needs no translation: their shared understanding of the language of form in the sculptures they carve.

On the walls hang photographs of the sculptures and figures that adorn Vallø Castle’s façade, visible through the small windows of the old courtyard house. The photos are pinned like a detective’s evidence board, marked with notes and dates connecting faces and details. Each sculpture is tracked through its various stages - a puzzle of past craftsmanship. The goal is to recreate the intricate details time has worn away, details Mette is now determined to bring back to life.

»There’s an incredible amount of sandstone work on the façades - nearly 300 life-sized heads looking out from the walls,« Mette explains.

Among the photos in the workshop is a printed image of a faded 16th-century figure from the grand portal of Voergaard Castle in Vendsyssel.

»Her name is Melusina, a character from Renaissance legends. She holds a mirror and a lock of hair in her hands, and in the corners there are two lion-like moon creatures,« Mette says, pulling out even more reference photos of the sculptures she’s working to restore.

»According to the story, she married a nobleman on one condition - that he would never see her on a Saturday. But curiosity got the better of him. One day he snuck in and saw her bathing in a tub, where her legs slowly turned into a tail. When she realized he had seen her, she transformed into a dragon and flew away,« Mette recounts.

When Cultural Heritage Crumbles

Mette has helped restore a long list of projects that leave most people speechless. For her work as a restoration architect, she received the prestigious Europa Nostra Award in 2015, honoring individuals who have made an exceptional contribution to preserving Denmark’s cultural heritage. Today, she uses that expertise to tackle the large backlog of maintenance threatening many of the country’s castles and manor houses with decay.

»Many of our castles were built around the same time, which means they’re deteriorating at the same time. Kronborg and Frederiksborg Castle are in severe decline, and with the Børsen fire on top of that, we’re facing a massive backlog. We have to act - otherwise people literally risk getting stones dropped on their heads,« Mette says.

Denmark’s stone-carving and sculptural traditions trace their roots to Saxony in Germany and the Netherlands, from which skilled sculptors and stonemasons were brought north during the Renaissance under Frederick 2. That’s where the Danish visual language and sculptural tradition originate. Nearly all Danish castles and manor houses were built from the late 1500s to the mid-1700s.

At the Vallø workshop, everything is carved in the traditional way - almost as it was when the pyramids were built. Sketches, plaster models, and half-finished, life-sized heads fill the space. There’s a kind of orderly mess in the room, and through the old windows you can glimpse the castle across the moat.

Several of the figures on the castle façade look related, as if they were members of the same family. Mette and her colleague Jens eagerly debate how Herman Stenmester, a 16th-century sculptor, conceived his details at Vallø Castle. Should the chain mail have more cutwork? Should the mouth be sharper or rounder?

From the workshop, we cross the moat and walk to the castle to study the ornamentation on the façade. Along the way, Mette shares another tale about Voergaard Castle, where she also works.

»There’s a story that the patron drowned the architect when the castle was finished, so no one else could have a palace as beautiful,« she says.

It quickly becomes clear that being a stonemason and restoration architect is also a form of detective work - a journey into history and the original intentions behind the ornamentation. At Vallø Castle, many of the 300 heads are so degraded that you can barely make out their original expressions. That’s why the figures are first reconstructed in plaster in close collaboration with art historians before they are carved in stone.

Sandstone - The Danish Marble

The distinctive sandstone has shaped Danish architecture since the Renaissance. Back in the 1500s, it was imported from Gotland, which at the time was part of the Danish realm.

»In Denmark, we never worked in marble the way they did in Italy. We had our own beautiful stone - the sandstone from Gotland. It just wasn’t very durable, so it was impregnated and painted white to look like marble.«

In the 19th century, everything changed when Romanticism swept through Denmark. The paint was stripped off to reveal the raw stone beneath, and acid was used in the process - something that, ironically, has accelerated deterioration today.

»That’s why so many of our buildings are now decaying at the same time. They were ‘undressed’ 200 years ago, and now we’re paying the price.«

Today, restorers use a silica-based sandstone from Germany, which can last up to 500 years without surface treatment.

»Stone is a primal material - something we can all relate to. The fact that we can create something within it, bring a face or a form out of solid rock - many people find that absolutely magical« Mette says.

3 Types of Stone

Granite

One of the hardest natural stones - dense, heavy, and almost impossible to scratch. It’s used for gravestones, stairs, foundations, and monuments. Working with granite requires significant physical strength and heavy tools.

Sandstone

A softer, more porous stone that can be shaped with great precision. It’s commonly used for sculptures, decorative details, and the restoration of historic buildings.

Marble

A dense, glossy stone formed from metamorphosed limestone. It’s associated with classical art and architecture - from ancient temples to Michelangelo’s sculptures. Relatively easy to carve, but it demands a refined sense for the stone’s structure and natural veining.