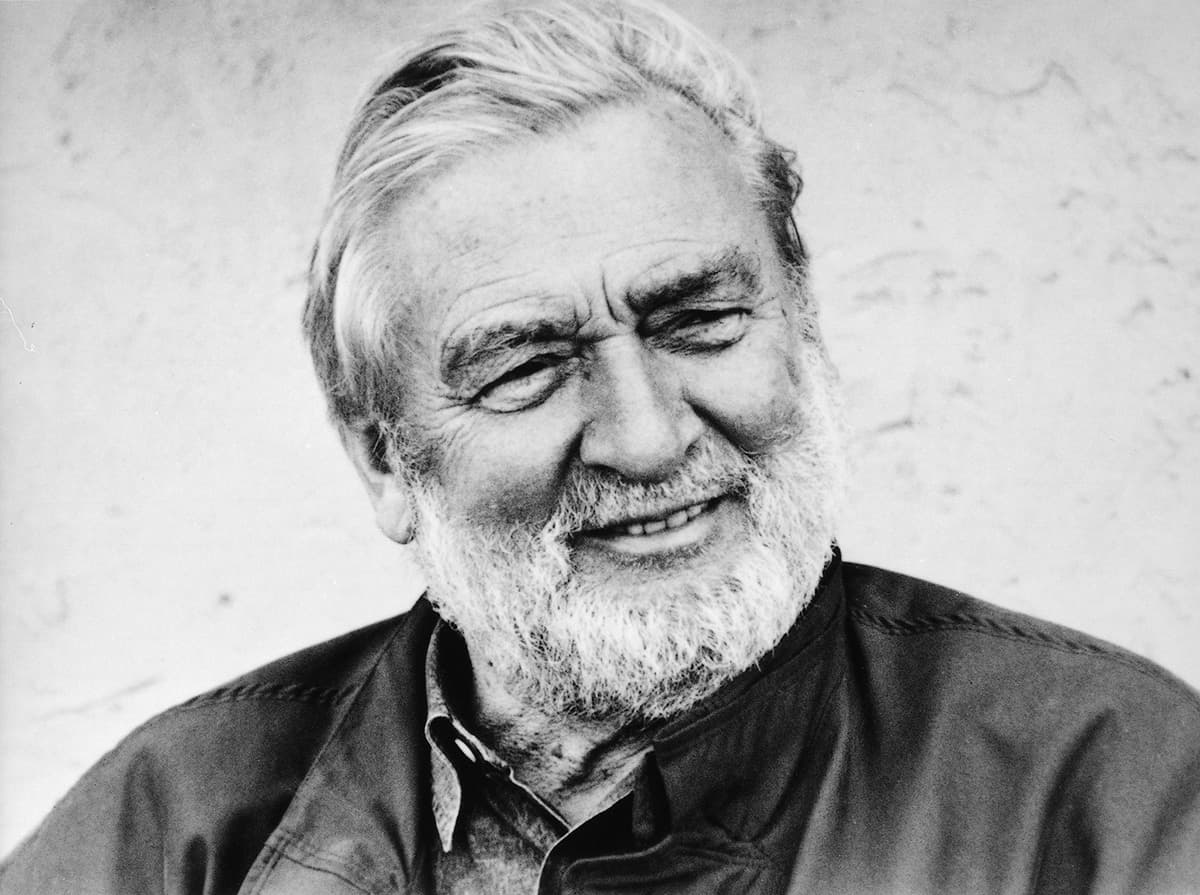

Verner Panton: 10 Designs You Simply Need to Know

Known for his bold colors, organic forms, and uncompromising vision, Verner Panton stands as one of the most radical figures in Danish design. Dive into 10 futuristic designs that take you through Verner Panton’s imaginative universe.

By Ida Elva Hagen

Verner Panton (1926–1998) had no patience for the world as it was. He designed as if the future had already arrived. While much Danish design of his time sought calm, continuity, and the natural, Panton insisted on rupture, color, progress, and the untested. That’s how Pernille Stockmarr – Senior Curator at the Danish Architecture Center – describes him.

Designing for the Future

»Verner Panton had no interest in refining history, but in challenging our habits and the way we live. By embracing plastic, glass, and steel – and by creating atmospheres where color became form and light became movement – Panton didn’t just design furniture and lamps; he created spatial universes where architecture and interior design merged into a single, cohesive experience,« she says.

According to Pernille Stockmarr, Verner Panton took popular culture seriously and fully embraced mass production. He envisioned imaginative futures in which the artificial and technology were not threats, but fundamental conditions of life.

Why We’re Still Talking About Panton

»Today, as our surroundings are once again up for negotiation – shaped by technology, climate change, and new social structures – Panton reminds us that design isn’t only about solutions, but about imagination and courage. It’s about daring to use architecture and design to test new ways of living – not as final answers, but as explorations of what we don’t yet know.«

Together with Pernille Stockmarr, we’ve selected some of Panton’s most distinctive designs.

Photo: Montana Panton One (1955)

Panton’s first mass-produced chair (1955) was commissioned by a restaurant in Tivoli and put into production by Fritz Hansen. The chair combines craftsmanship and industry, revealing his early interest in lightness, repetition, and structural clarity. Viewed through a contemporary lens, it appears as a transitional work – one that points toward his later radical experiments. It was later renamed from the Tivoli Chair to Panton One.

Photo: Vitra Cone Chair (1958)

Designed for his father’s restaurant, “Kom Igen,” in 1958, the Cone Chair marked the foundation of Panton’s future design direction – a bold yet disciplined style that modernized basic geometric forms. The chair is made from a thin sheet of metal, gaining its structural strength from being folded into a cone shape. Upholstered in foam and covered in wool, it was made comfortable as well as striking.

In collaboration with the company “Plus-Linje,” which exclusively produced and distributed Panton’s designs, Verner continued developing the concept into a full furniture series, including the 1959 “Heart Cone” chair, now considered one of his classics.

"Verner Panton had no patience for the world as it was. He designed as if the future had already arrived."

Photo: VERPAN Moon Lamp (1960)

One of Panton’s earliest lighting designs and an important step toward his later experiments with light and space. The circular lamellae can be adjusted, creating a dynamic interplay of light and shadow. The lamp reveals Panton’s fascination with light as an active, space-defining element.

Photo: Vitra Panton Chair (1967)

With its iconic S-shaped silhouette in plastic, Verner Panton offered an early glimpse of the future. The idea emerged in the late 1950s, but it wasn’t until 1967 that the chair finally went into production after years of material experimentation. The result was the world’s first cantilevered chair made from a single piece of plastic – a symbol of pop design and new manufacturing possibilities. It was later introduced in more affordable versions, and today the popular chair is still produced by Vitra.

Photo: Louis Poulsen Flowerpot (1968)

After its debut at the first Visiona exhibition in 1968, the Flowerpot lamp immediately went into production with Louis Poulsen. Its two hemispherical shades create soft, indirect light and a simple, graphic silhouette. The lamp became a symbol of the era’s optimism and Panton’s ambition to bring color and form into everyday life.

Photo: VERPAN VP Globe Lamp (1969)

A spectacular lamp that can easily be mistaken for a soap bubble or a UFO hovering in space. The VP Globe consists of a transparent acrylic sphere, with the distribution of light controlled by a system of internal reflectors. Once again, Panton combines system and industry with simple, organic forms – an interplay that illuminates and defines the shapes and colors of the surrounding space.

Photo: © Verner Panton Design AG Fantasy Landscape – Visiona II Exhibition (1970)

With Fantasy Landscape, Panton created a total environment in which floors, walls, ceilings, and furniture were shaped into one cohesive, organic whole. Designed for Bayer for the 1970 Cologne trade fair, the installation embraced Panton’s vision of an environment that envelops people and shapes their experience within it. Here, the boundaries between architecture, furniture, light, color, and human behavior dissolve. The exhibition functioned as an experiment in new ways of living and inhabiting space – more sensory, flexible, and less bound by the traditional home.

Photo: © Verner Panton Design AG Interior Installation – Varna Restaurant (1971)

The Varna Restaurant stands as a key example of Panton’s idea of design as a total experience. Here, he worked with the entire room, allowing furniture, textiles, colors, and lighting to merge into a single sensory environment – a true gesamtkunstwerk. The space was conceived as an active participant in guests’ experiences and social interaction, clearly illustrating Panton’s vision that interiors can influence behavior, mood, and relationships.

Photo: Montana Pantonova Sofa (1971)

The Pantonova wire furniture was created specifically for the interior of the Varna restaurant in Aarhus in 1971. Pantonova demonstrated Panton’s modular thinking – it wasn’t a single piece of furniture, but an entire system. The modules can be combined in endless shapes and configurations, clearly expressing Panton’s belief that furniture can support new social patterns and behaviors. The Pantonova sofa later achieved international fame when it appeared in the 1977 James Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me.

Photo: Louis Poulsen Panthella (1971)

Panthella is a prime example of Panton’s human-centered approach to lighting. Its organic form conceals the light source and softly reflects the light in both the shade and the base. The result is warm, even illumination, where function and form merge into a unified expression. It was introduced in 1971 as both a table and floor lamp, and in 2016 it was further developed in a smaller version.

More from DAC Magazine

DAC Magazine

Verner Panton Rebelled Against Sharp Lines and the Color White

Regulars, Hidden Gardens, and Funky Functionalism in the Inner City: »People often ask me to show them things they’ve never seen before.«

Designer Nanna Ditzel Created Color, Function, and Imaginative Solutions

When Buildings Come Alive: The Future of Architecture May Be Grown, Not Built