Amateur Architecture Studio: Building Slowly in a Fast World

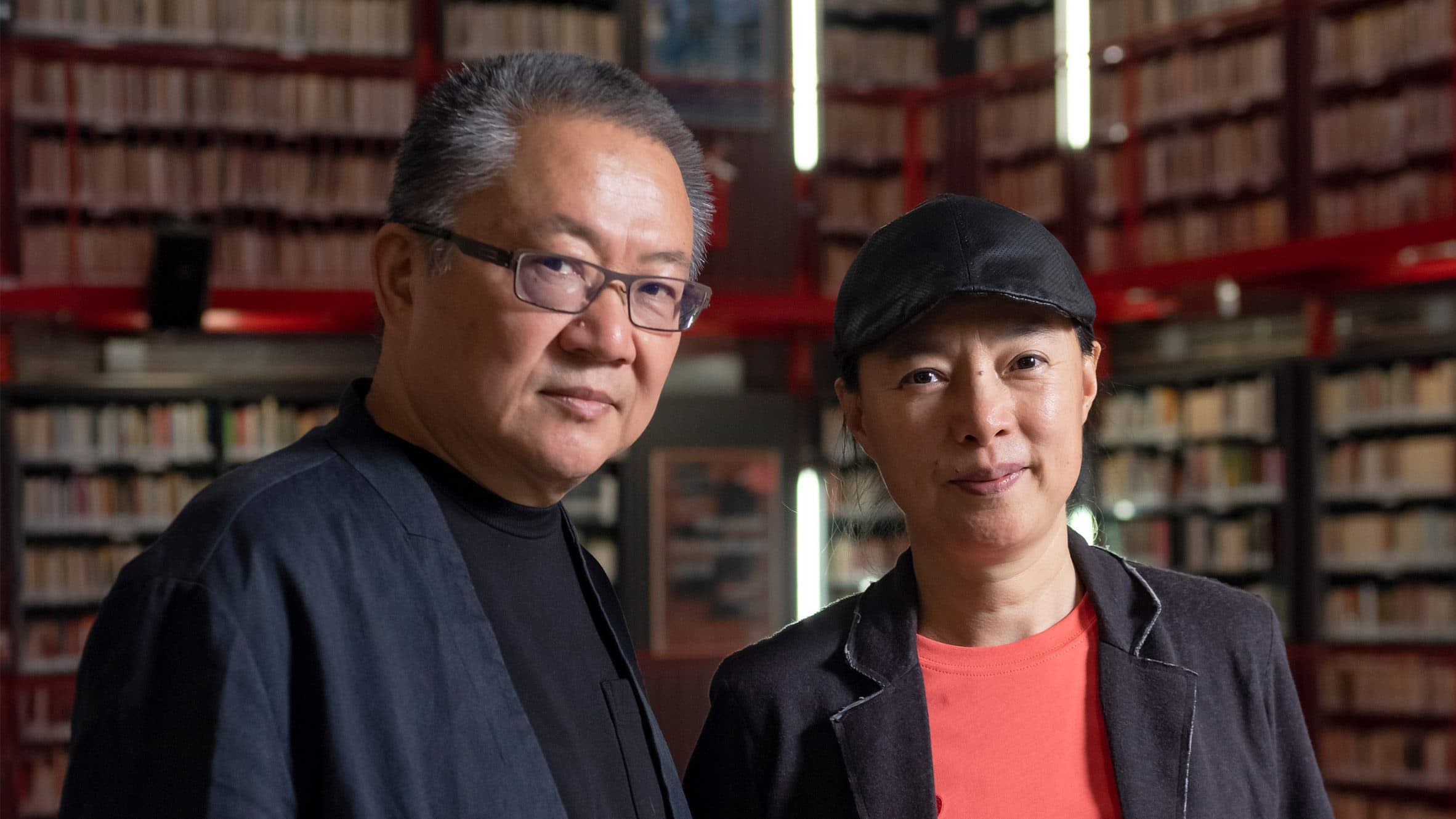

Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu are behind the Chinese firm Amateur Architecture Studio. They create architecture rooted in place, drawing on reuse, tradition, and lived experience – as a challenge to the construction boom and history-less assembly-line architecture.

By Andreas Grubbe Kirkelund

The rough wall of the Ningbo History Museum is composed of rubble, shards, and bricks that vary in color and age – almost as if they were just dug out from the ground. Locals say they can recognize fragments of their former homes embedded in the masonry. The wall is built from pieces of demolished buildings. In a sense, it is built from the past – shaped into a form of the present.

Amateur Architecture Studio, led by the two Chinese architects Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu, designed the museum with its uneven, rugged facade. The building clearly expresses the firm’s intention to resist the explosive construction frenzy that, in just a few decades, has transformed large parts of China. In an era defined by speed, speculation, and standardization, they insist on slowness, craftsmanship, and a close relationship to place.

One partnership. Two temperaments

Wang Shu grew up with an intuitive approach to form and space and spent his early years on construction sites, where he learned traditional craftsmanship directly from masons and carpenters. Lu Wenyu came from a different background: sharp technical precision and an aptitude for large, complex projects, developed through work at a national design institute. Together, they founded Amateur Architecture Studio in 1997.

The duo’s close collaboration became especially visible when the world’s most prestigious architecture prize, the Pritzker Prize, was awarded to Wang Shu in 2012 – even though the projects on which the prize was based were developed jointly with Lu Wenyu. The decision drew criticism from several quarters, pointing out that it reflected a broader tendency: successes are often attributed to a single named architect rather than to a partnership or collective effort.

Lu Wenyu did not comment publicly on the matter and is generally known for staying out of the spotlight. Wang Shu, however, consistently describes Lu Wenyu as his only partner and emphasizes that their projects are created exclusively together.

"We don’t have earthquakes – we are earthquakes!"

The Amateur as the New Hero

The name Amateur Architecture Studio may sound self-contradictory for an internationally recognized architecture firm – some might even consider it ironic or unserious. In reality, it is a core ideological principle. For the duo, “amateur” is not the opposite of skill. An amateur is someone who practices out of passion.

»Expert sounds boring. Amateur sounds ideal and multi-talented. And he loves his work,« Wang Shu told CNN in a 2017 interview.

But the amateur is about more than passion. It represents a particular approach to architecture that grows out of craftsmanship, materials, and specific places – rather than abstract concepts. The amateur symbolizes spontaneity and experimentation and stands in sharp contrast to the official, monumental architecture that dominates much of the construction industry – not only in China, but across much of the world.

For Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu, the amateur is therefore a critical figure. It represents an architecture grounded in everyday life, human scale, and local experience – one that can only emerge through a practice in which the architect works closely with craftspeople, traditional techniques, and the inherent logic of materials.

Urbanization Erased History

China’s modernization has come at a cost. In many major cities, almost all traditional buildings have been erased within just a few decades. In an interview with PIN–UP Magazine, Wang Shu has described the process with a striking metaphor:

»We don’t have earthquakes — we are earthquakes!«

This extreme transformation does not only mean the loss of buildings, but also the loss of identity. When new districts are built all at once, marked by international styles and “global” high-rises, cities emerge that could be anywhere. The result is a loss of cultural continuity and of the everyday life shaped by small variations: a particular brick, a shadow on a roof, a view toward a mountain, a narrow passage between two houses.

Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu position themselves as a response – or a counterweight – to this development. Not because their architecture is backward-looking, but because they insist that the new should not be built by erasing what already exists.

About Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu

Wang Shu (b. 1963) and Lu Wenyu (b. 1967) are partners – professionally and privately.

Both studied architecture at Nanjing Institute of Technology.

Founded Amateur Architecture Studio in Hangzhou in 1997.

They have exhibited internationally, including at MoMA, the Centre Pompidou, and in Denmark at Louisiana.

They have received numerous international honors, including the Schelling Architecture Prize in 2010 and the Pritzker Prize awarded to Wang Shu in 2012.

Their previous contributions to the Venice Architecture Biennale include Tiled Garden (2006) and Decay of a Dome (2010).

The duo has been appointed as chief curators of the Venice Architecture Biennale 2027.

The Amateur’s Method is Slow

Amateur Architecture Studio takes on only a few commissions at a time, because their projects require an extraordinary amount of time and involvement. They conduct countless full-scale experiments, prototypes, and tests – using both old and new techniques. Everything is supported by close dialogue with craftspeople, who often contribute local twists or “secrets” to the project.

This approach is both radically old-fashioned and deeply experimental. It differs from much contemporary architectural production by prioritizing presence over efficiency and by allowing the construction site to function as a laboratory, where architecture is negotiated and shaped in real time.

Reuse as the Memory of Buildings

For the architectural duo, materials form the first narrative layer. Reused materials are not hidden away in internal structures. Instead, they often employ a building tradition that has shaped Chinese villages for centuries: walls constructed from broken bricks, roof tiles, and ceramic shards from demolished houses.

These fragments are laid in layers of mortar, creating a vibrant, irregular rhythm that can only emerge through craftsmanship and continuous judgment on site. When Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu use this technique, it is both to preserve a craft tradition and to embed traces of the old within the new. Bricks, stones, and timber from demolished houses carry the marks of human stories. Places and lived lives are held within the architecture.

Architecture Does Not Have to Be Loud

In a world defined by accelerated construction, globalized aesthetics, and increasing pressure on both climate and cultural heritage, Amateur Architecture Studio points to another path. It is slower and more demanding – but also more deeply connected to places and people.

Their buildings do not seek to be spectacular or loud. They aim to be honest and grounded in place. They show that architecture can be a way of remembering – of resisting the erosion of memory while simultaneously creating new frameworks for life.

Not because Amateur Architecture Studio is a nostalgic project, but because they insist that the future can be built from more than new concrete and fast decisions: from time, materials, hands, and memory.

Notable Projects

Wencun Village renovation (2015)

How a village can be renewed without turning into a museum. Existing houses are preserved and reinforced, new houses are built in rammed earth and bamboo, and the village’s traditional density is maintained to protect agricultural land. It is a model of rural modernity that offers hope at a time when villages are being emptied.

Ningbo History Museum (2008)

A structure that appears almost like a man-made mountain. The facades consist of millions of reused bricks and shards, assembled in patterns and rhythms that feel both ancient and contemporary. It is a museum built from the villages that had to give way to urban development – an architecture that makes loss visible and tangible.

Xiangshan Campus, China Academy of Art (2007)

A campus conceived as a large, branching village. More than 30 buildings are set on terraces in the landscape, connected by narrow streets, stairs, bridges, and courtyards. Built with millions of reused stones, it functions both as an educational institution where materials, craftsmanship, and the physical reality of architecture are integral to learning.