Photo: Jens Clemmensen

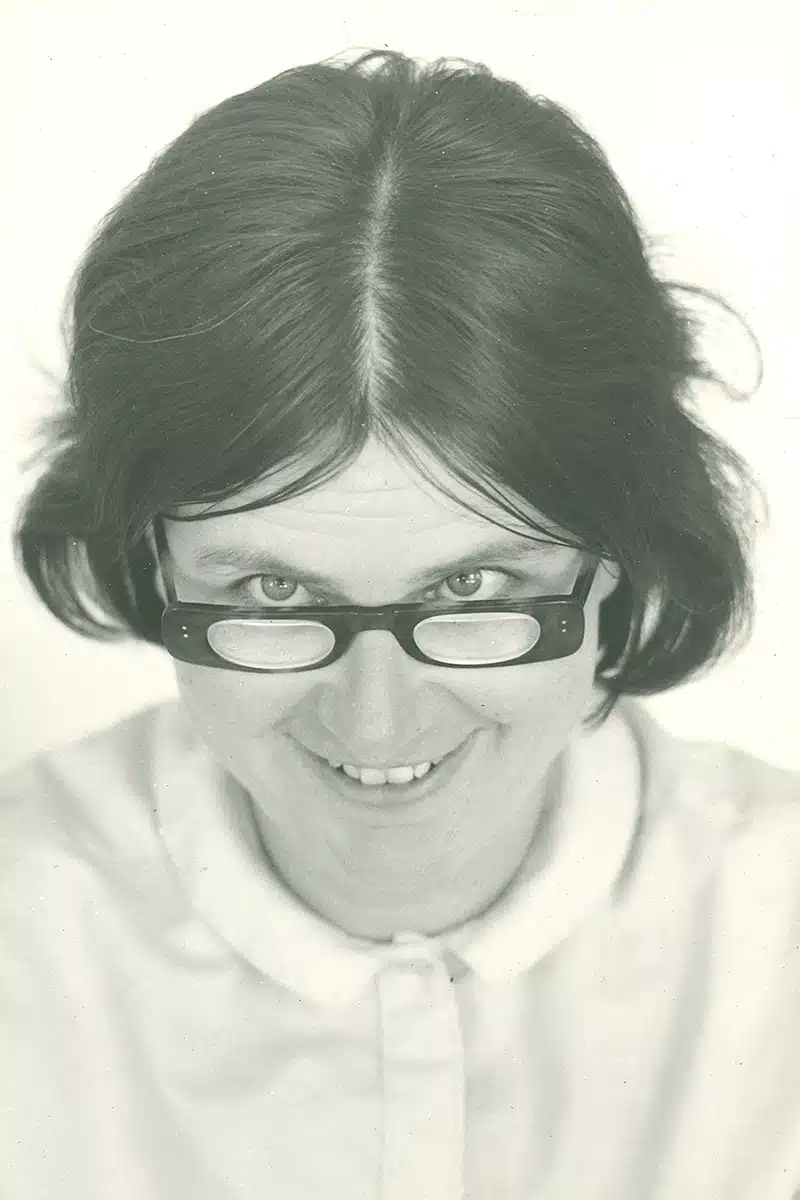

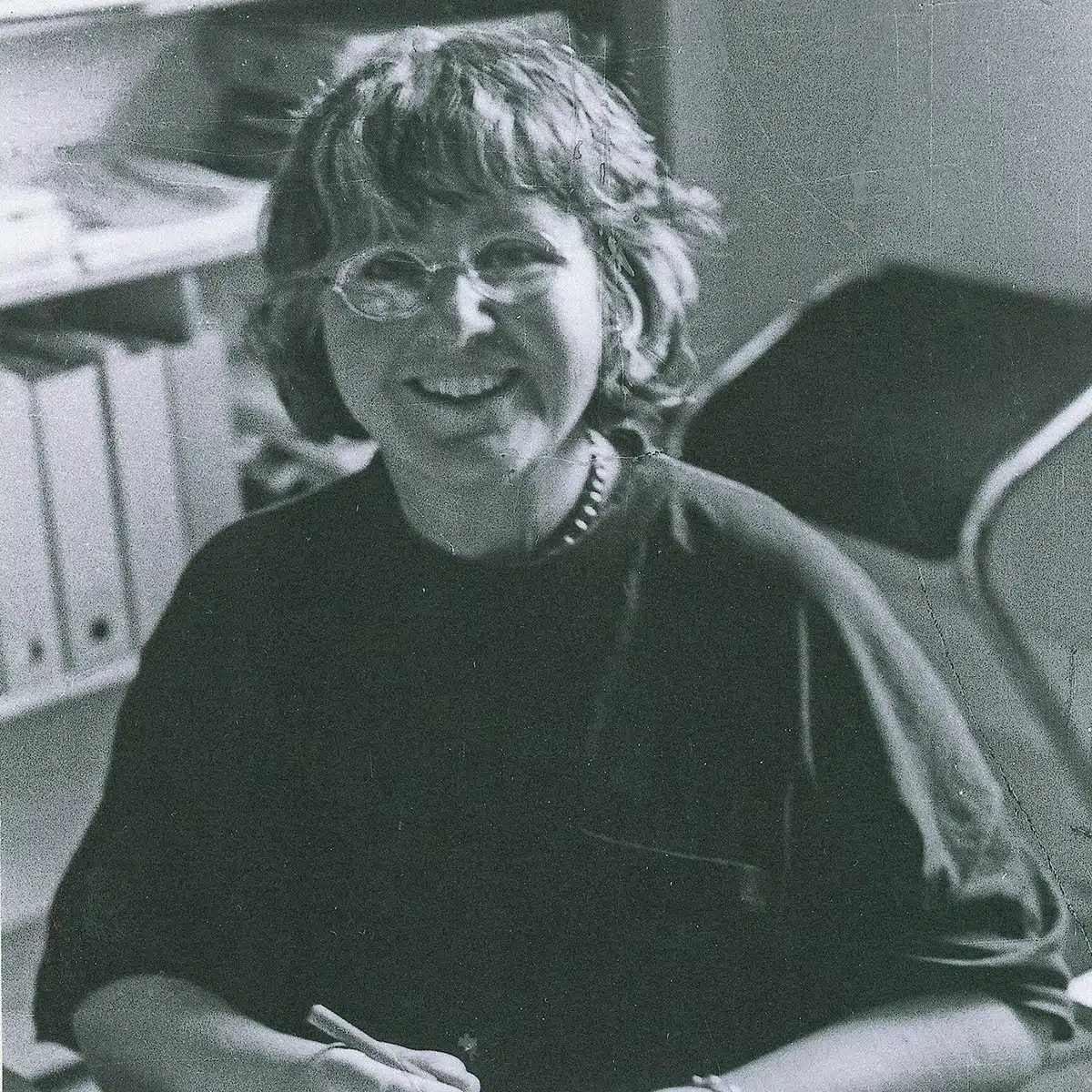

Portrait: Architect Karen Zahle Doesn’t Tolerate Things Getting Too Square

By Karla Clemmensen

August 21, 2024

Karen Zahle is one of many female architects who have not received the same level of recognition as their male counterparts. However, this has never stopped the now 93-years-old Karen Zahle from challenging conventional thinking in the world of architecture, even as gender inequality has sharpened her resolve.

In inner Copenhagen, on the corner of Gothersgade and Rømersgade, right across from the Botanical Garden, stands an old red brick building. The sharp corner of the property has been cut off and replaced with large windows. The light must be fantastic, I think to myself.

The building’s gable has the name ‘Kunstnerhjem’ (Artist’s Home) carved into a smooth stone, and I quickly connect the large windows with studios, imagining how creative souls throughout time have had both space and light to flourish in each apartment.

I press the name Karen Zahle and am buzzed into the hallway.

On the other side of the door, it feels like standing in the foyer of an old Parisian building. The marble floor echoes beneath me as I ascend the broad staircase, my hand resting on a finely polished wooden railing, likely made from a wood that was either expensive, rare, or perhaps both.

Engagement Plastered Directly on the Door

Standing in the doorway on the first floor is 93-year-old Karen Zahle, wearing a red knit cap and Icelandic sweater, warmly welcoming me. Her front door is wooden, framed by panels of colored glass, through which silhouettes that might once have been visible are now impossible to discern. Stickers cover the door—some with activist messages, others from cultural institutions, and a few with cheeky remarks. Some are at least 30 years old, while others have been added in the past few years.

Karen Zahle has lived in the building for more than 50 years. As she sets out the tea service on a round table in the corner of one of the apartment’s grand living rooms, she tells me that the house was built by an architect named Ferdinand Meldahl with the intention of creating homes for visual artists and architects. Karen Zahle pauses to ask if I’d like fresh lemon in my tea.

»Yes, please,« I reply, as she shuffles off to the kitchen in her wool slippers. She seems comfortable in her role as hostess.

A CV as Long as a Mile

After what feels like just a few minutes, Karen Zahle returns, placing a bowl of lemon wedges on the table. She settles into the chair, which she somewhat sharply refers to as hers, and enthusiastically picks up where she left off.

»Ferdinand Meldahl was a prominent figure in Danish society, especially in creative circles. And he was involved in everything here in Copenhagen. He was a member of the Academy Council, the City Council, the board of the Architects’ Association—you name it,« Karen Zahle says with admiration.

As I listen to the story, I can’t help but think how easily it could be about her. The first time I read about Karen Zahle’s accomplishments, I thought she epitomized what it means to be a passionate individual. In addition to her extensive work as an architect, she has also been a teacher, owner of her own design studio, exhibition organizer, and author of both research articles and opinion pieces.

The list of councils, associations, and boards she has been a member of is just as long. And it seems that only age has slowly tempered her engagement.

I share my comparison with her, and she responds with a humble laugh, explaining how her résumé, as she politely calls it, has grown so long.

»Well, you see, being on a council or board is a really good way to have some influence over things. And there, I could present my opinions, ideas, and solutions well-prepared,« Karen Zahle explains as she slowly squeezes the last bit of lemon juice into her tea.

A Dream Takes a Turn

Given her deep involvement in the field of architecture and her upbringing by parents with a background in the visual arts, it might seem inevitable that Karen Zahle would become an architect. But that wasn’t the case. After high school, where she majored in Greek and Latin, she dreamed of becoming a classical archaeologist. However, that dream was short-lived. Karen Zahle recounts how, after meeting with an archaeology professor at the National Museum in Copenhagen, she realized there wouldn’t be much stable work after graduation.

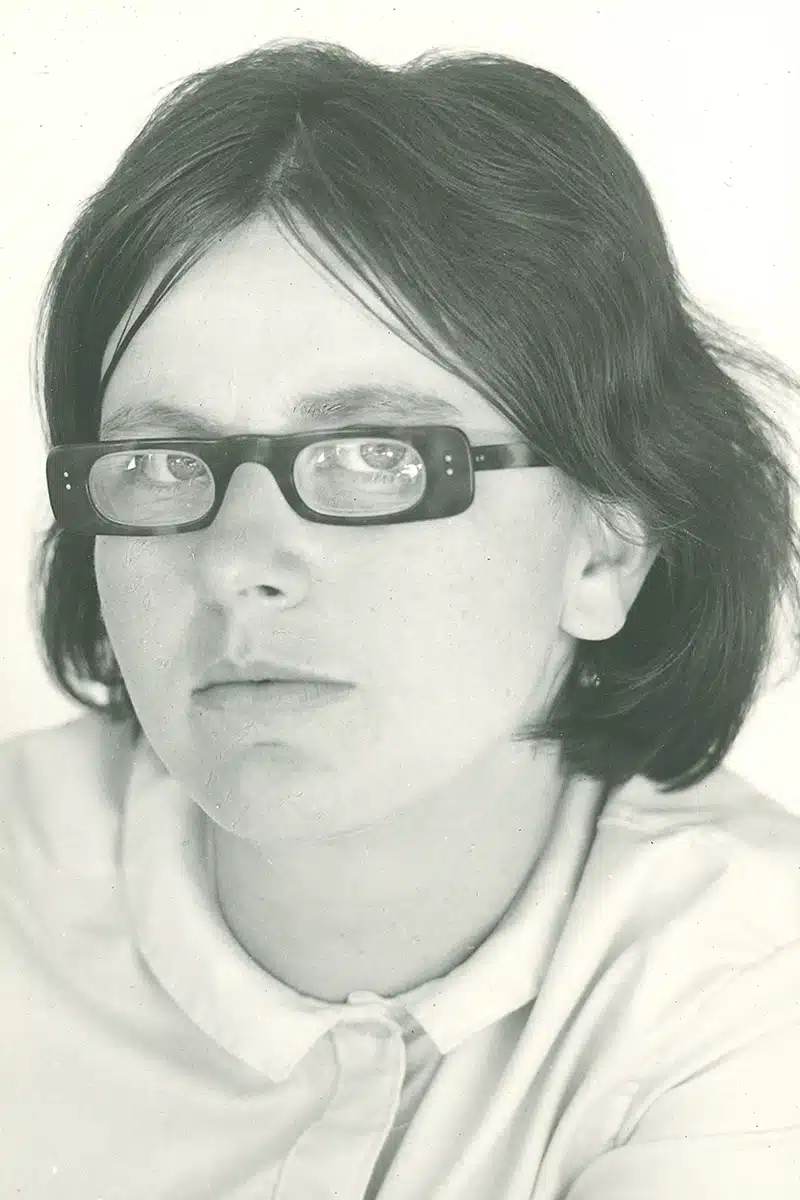

Photo: Privat

Meanwhile, her need for a more social life and her growing interest in art and culture, something Karen Zahle attributes to her parents’ creative background and their many friends among artists and architects, led her down a different path. She recalls how these friends were quite the lively bunch.

In 1952, 21-year-old Karen Zahle applied to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture.

Predictions of a Negative Nature

Although Karen Zahle mostly remembers her time as a student fondly, there’s no denying that the field of architecture was male dominated at the time. And the teaching in the old premises at Charlottenborg in Copenhagen made this clear.

»There weren’t generally many female students at the school. I think there were about 40 of us in our year, and we were split into two groups. In my group, there were five women,« says Karen Zahle, noting that most of the instructors at the school were also men. However, this didn’t significantly affect her experience as a student.

Her tone shifts, though, when discussing the expectations for the relatively few women in the program.

»For a long time, female architecture students were either predicted to drop out of the program, or it was assumed that motherhood and family life would eventually put an end to their careers,« Karen Zahle explains, adding that it was extremely difficult for women to make their mark in the field of architecture at the time.

But nothing stopped Karen Zahle from graduating from the School of Architecture in 1959.

The Neat, Gray Suit Trousers

As a newly minted architect, Karen Zahle was deeply interested in the social orientation of the field, which focused more on people. She was particularly drawn to housing and interior design, which she felt could be exclusionary toward alternative living arrangements like co-housing and communes.

However, these were not the topics that dominated her early years at the architecture firm of Palle Suenson. Nonetheless, she was happy with the job—a position many of her fellow graduates coveted. It was a well-regarded firm, and as a new graduate, it was a great opportunity.

Karen Zahle recalls that everything was very strict—a word she later replaces with boring. This applied not only to the architecture being developed at the firm, where the concept of ‘Less is more’ was strongly emphasized, but also to the social life among colleagues. They all wore what Karen Zahle describes as neat, gray suit trousers, which didn’t live up to her expectations. So, Karen Zahle decided to return to a more socially oriented approach.

Closer to the People

That same year, she was hired by the Ministry of Housing, where a department had been established to address some of the issues that had been neglected during the war. Karen Zahle was to help ensure that proper housing developments and urban planning were in harmony with the types of buildings municipalities wanted to construct.

»Before municipalities got into the details and made local plans, they were required to create a master plan, which we architects would then go out and comment on and evaluate,« Karen Zahle explains.

The office consisted of a group of experienced, slightly older architects and their juniors, and Karen Zahle was one of those juniors.

She remembers her time at the Ministry of Housing as exciting and educational. The trips to provincial towns in Denmark, where they had to evaluate various proposals, stand out clearly in her memory. But it was also a time of frustration and a feeling of being overshadowed by the more experienced architects, as she stood with her notepad and pencil, itching to contribute. Karen Zahle wasn’t always in agreement with what was being presented, but her alternative solutions, which focused more on aesthetics, were rarely heeded.

A Bicycle Turned into Art

Karen Zahle has followed my gaze, which has stopped at an unusual chandelier, from which a lot of colorful trinkets hang down.

»Can you see what it’s made of?« she asks me.

As my eyes struggle to find the answer, Karen Zahle begins to explain that the many different parts actually come from a bicycle, and suddenly I can see both wheels and chains. The decorations, which include old Christmas ornaments made by Karen Zahle’s own mother and souvenirs from various places, are things she added later.

It suddenly becomes clear why Karen Zahle didn’t feel at home among neat, gray suit trousers.

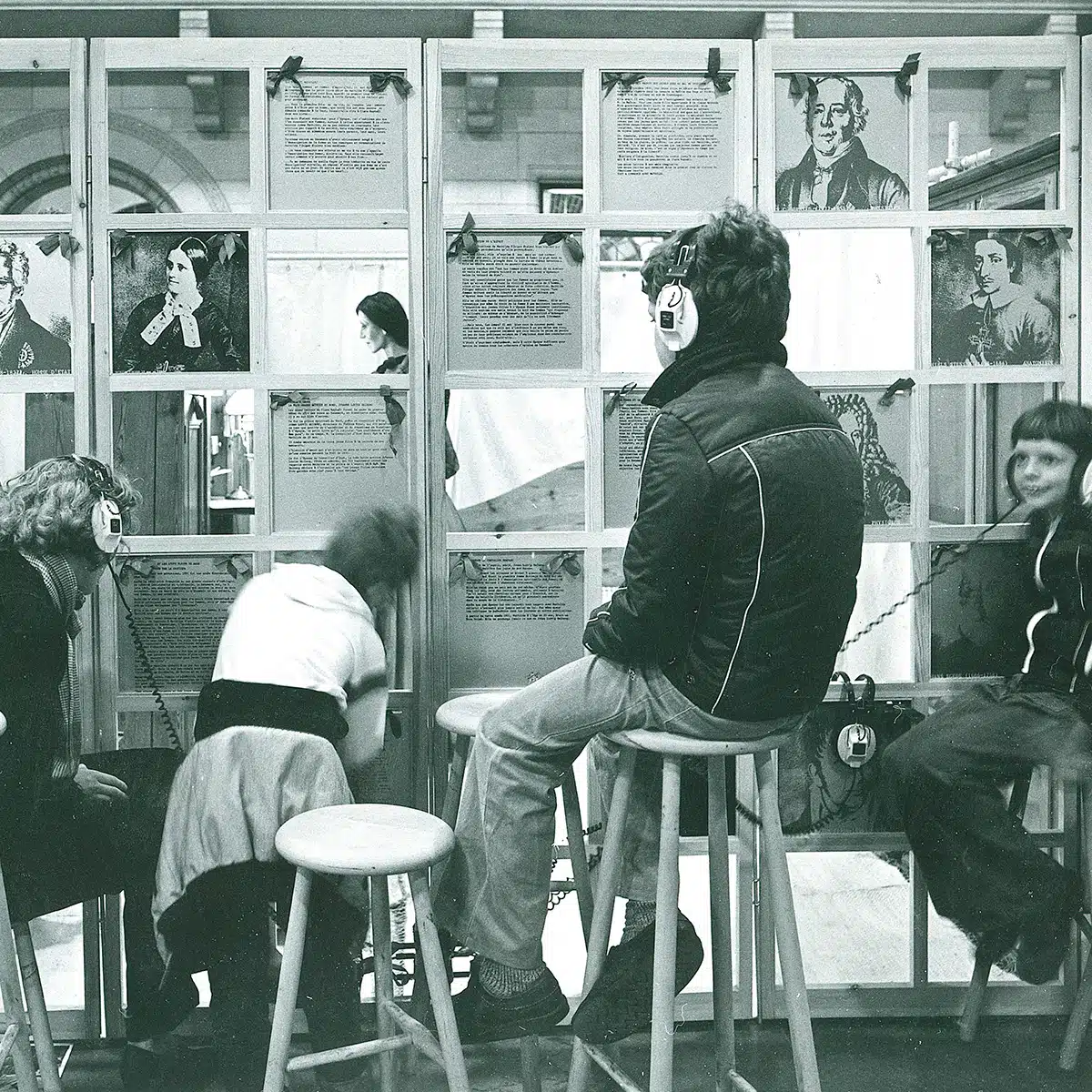

Photo: Lillian Bolvinkel

Room for Bigger Gestures

In her early 30s, Karen Zahle got a job at Anne Marie Rubin’s architecture studio in Nyhavn, which shortly thereafter moved to Holte, and here she felt at home. The studio allowed for larger gestures, which took place on the other side of the table compared to what she had been used to at the Ministry of Housing. For Karen Zahle, this was an exciting change.

Urban planner Anne Marie Rubin was one of the few women to start her own architecture firm, where she held her own against men. Rubin was a talented woman with a strong will, who was also involved in women’s issues. She was someone the younger Karen Zahle greatly admired.

»Anne Marie Rubin was very aware of the existing gender equality issues in society, which led her to engage in women’s issues both within and outside the field of architecture,« Karen Zahle explains.

She notes that Anne Marie Rubin’s general views inevitably influenced the projects at the studio, and Karen Zahle is convinced that this also played a role in her own well-being at the workplace in Holte.

A Slightly Offbeat Discovery

I take advantage of a bathroom break to look around. At the end of one hallway, behind a half-open door, is the kitchen. And here, I can’t help but smile. Most of the kitchen modules have been shifted a few degrees out into the room, no longer aligned with the wall but instead standing askew in the narrow space. Could this be Karen Zahle’s way of challenging some norms in architecture? Or is it the work of someone who just isn’t very fond of boxes?

Later, Karen Zahle explains that the layout of the kitchen has made it easier to create social interactions while cooking. You have the option to stand on multiple sides of the modules, all of which face the small, round dining area at the end of the room. And it has also served as a good vantage point for single parents with children who have trouble sitting still, Karen Zahle adds with a small smile.

Interdisciplinarity Becomes a Buzzword

When Karen Zahle became pregnant in 1968, she needed more stability. At that time, she had started a design studio with Søren Koch, whom she knew from her time at the academy. Together and individually, they created exhibitions, often about architecture, and Karen Zahle also worked as a part-time teacher at the School of Architecture.

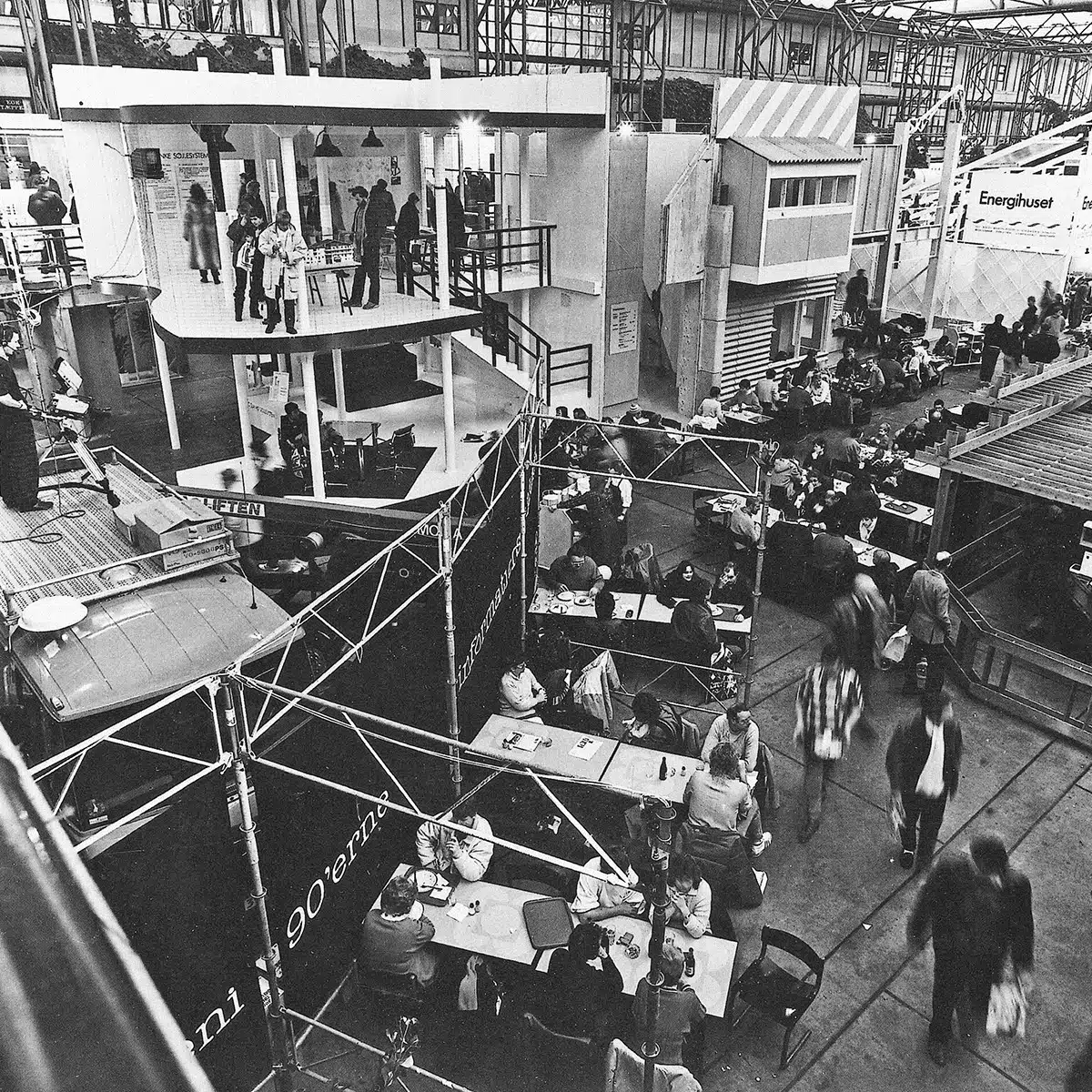

Photo: Privat

From her maternity bed at Rigshospitalet, she applied for a three-year scholarship at the School of Architecture, which could help bring some more stability to her life—and she got it. At that time, Karen Zahle was deeply interested in ergonomic design, which was also reflected in her application.

Her interest in ergonomics had already begun blossom back when she met the father of her son, a skilled doctor who introduced her to a whole new world. During their relationship, she met people who, like her, were interested in how architecture and design can affect people both physically and psychologically, albeit from a medical perspective.

»Interdisciplinarity became a buzzword at that time. You weren’t expected to know everything, but you could contribute your expertise in collaboration with others,« Karen Zahle explains.

She uses the chair as an example of an indispensable object for humans. An object, that is now designed in collaboration with various professionals depending on the intended use. As she speaks, Karen Zahle lightly runs her hand over the back of a wooden chair next to her, demonstrating how design has a significant impact on our comfort and well-being.

A moment later, Karen Zahle firmly places her palm on the table, emphasizing that increased focus on functionality should never come at the expense of aesthetics.

A Groundbreaking Project

After three years as a researcher, Karen Zahle returned to her previous position at the School of Architecture. In 1980, she became the head of the Housing Laboratory, a position she held for 20 years. There, in collaboration with practicing architect Peder Duelund Mortensen, she created the 1:1 Laboratory, where students, in dialogue with various professionals and public authorities, would build full-scale models of upcoming buildings in Copenhagen. The process was followed by user surveys to see if there was anything that could be developed differently for more suitable design.

Photo: Privat

Although the Housing Laboratory was demanding in terms of resources and space, the team always found solutions. To address the lack of space, for example, it was decided that the 1:1 models should initially be built in the Grey Hall at Christiania. Most of the funding came from various private foundations.

Moreover, the high unemployment rate in the 1980s ironically proved to be a huge advantage for the project, as it provided access to cheap labor, with many of the laboratory’s unemployed workers being temporarily hired with state subsidies. Karen Zahle calls it a good way to help each other out.

The Elderly Must Be Included Too

Karen Zahle retired from the workforce in 2001, but her heart still belonged to the profession, and now she had more time to get involved in various councils and associations. Around the time she left the Housing Laboratory, she became chair of the Academy Council, a position she had been a member of for several years. She held this post for three years.

Photo: Privat

Later, Karen Zahle led an interest organization within the Architects’ Association for nearly twenty years: a Senior Network where retired members and employees of the association can still engage with the profession through excursions, overseas trips, and lectures. She explains that the network was established because seniors can feel excluded from the field of architecture when they navigate it on their own, so there’s a need for organization.

»It’s easier to reach out on behalf of a group rather than just yourself when you want to visit companies and design studios,« Karen Zahle explains.

Today, Karen Zahle is only involved in a book club. But that doesn’t mean that architecture plays a smaller role in her daily life. She calls contemporary architecture a very confusing landscape and elaborates by pointing to two female star architects, Dorthe Mandrup and Lene Tranberg, who, according to Karen Zahle, are both extremely talented and yet very different. However, it is precisely these differences that contribute to making modern architecture exciting, she emphasizes.

Karen Zahle herself plans to visit the Opera Park soon. She visits Copenhagen’s new architecture and urban spaces while observing city life as soon as she can. These trips are always accompanied by her walker because, although her body isn’t what it used to be, Karen Zahle’s curiosity is still alive and well.

A True Passionate Soul

With one foot halfway out of Karen Zahle’s apartment, no longer illuminated by the day’s sunlight, I catch a glimpse of a book titled Copenhagen’s Old Baths by Helen G. Welling, peeking out from under today’s newspaper. She immediately picks up on my curiosity and tells me the book is brand new and really fascinating.

As I quickly flip through the first few pages, I tell her that I’m on my way to Sjællandsgade Bathhouse to use the sauna—an old public bathhouse in Nørrebro, originally built to provide Copenhageners with bathing facilities. Karen Zahle listens intently, but as I talk, I sense an eagerness to take back the conversation. However, it doesn’t take long before she stops herself. Karen Zahle realizes that the story she’s about to share would likely take up most of the evening. Instead, she asks if she can join me next time. She explains that she would love to visit such an old Copenhagen bathhouse.

About Karen Zahle

- Born: December 23, 1931

- In 1959, Karen Zahle graduated from the Royal Danish Academy – Architecture

- In 2004, she was awarded the Academy Council’s Jubilee Medal

- In 2012, she became an honorary member of the Academy of Fine Arts

- In 2021, the book Excluded and Enclosed – Architect Karen Zahle, written by Kim Dircknick-Holmfeld and Anja Lollegaard, was published